By: Meg Wickless

In January of 2016, I began working with the vanEngelsdorp Bee Lab as an undergraduate researcher. I’ve really enjoyed the past year and a half of learning about the biology and management of honey bees, and working under the vanEngelsdorp lab has provided me with a lot of new and exciting opportunities. Perhaps the most exciting of these opportunities has been the chance to conduct my own honors research project.

This is a three-semester-long endeavor, where I will come up with my own research project, carry this project out, and ultimately defend my thesis in front of the University of Maryland Honor Board. As of now, May 2017, I am finishing up the first part of this process: developing my own research project.

This is a three-semester-long endeavor, where I will come up with my own research project, carry this project out, and ultimately defend my thesis in front of the University of Maryland Honor Board. As of now, May 2017, I am finishing up the first part of this process: developing my own research project.

Coming up with an entire research project that is unique, relevant, and, most importantly, possible for an undergrad, is a daunting task. After weeks of reading through recent journals about honey bees, discussing ideas with people around the lab, and almost losing hope of ever coming up with something doable, I was able to develop a project and research plan: “Effects of Age-Related Exposure to Fluvalinate on Learning and Memory in Honey Bees.”

Learning and memory in honey bees is vitally important to a colony’s health. Honey bees depend on their ability to learn and remember landmarks and celestial cues in order to find their way to and from food sources. When bees return to the colony after foraging, they must remember detailed information about food sources so they can communicate this information to other foragers.

At first it may seem like a challenge to quantify a honey bee’s ability to learn and retain information. However, in 1961, Kimihisa Takeda developed a method to do just this. Takeda’s method is called Proboscis Extension Response (PER) conditioning. PER is a method of classical conditioning that can be used to assess the learning ability and memory retention of honey bees. Under normal circumstances, if a drop of sucrose solution is touched to a bee’s antenna, it will reflexively extend its proboscis. Below is a video I took of the bees responding to the sucrose solution with proboscis extension. PER takes this behavior and pairs it with an odor stimulus, so that the bee will learn to associate extending its proboscis with the odor, and not with the sucrose solution. The bee’s ability to make this connection is used as an indicator of its ability to learn.

Learning and memory in honey bees is vitally important to a colony’s health. Honey bees depend on their ability to learn and remember landmarks and celestial cues in order to find their way to and from food sources. When bees return to the colony after foraging, they must remember detailed information about food sources so they can communicate this information to other foragers.

At first it may seem like a challenge to quantify a honey bee’s ability to learn and retain information. However, in 1961, Kimihisa Takeda developed a method to do just this. Takeda’s method is called Proboscis Extension Response (PER) conditioning. PER is a method of classical conditioning that can be used to assess the learning ability and memory retention of honey bees. Under normal circumstances, if a drop of sucrose solution is touched to a bee’s antenna, it will reflexively extend its proboscis. Below is a video I took of the bees responding to the sucrose solution with proboscis extension. PER takes this behavior and pairs it with an odor stimulus, so that the bee will learn to associate extending its proboscis with the odor, and not with the sucrose solution. The bee’s ability to make this connection is used as an indicator of its ability to learn.

Video of bees responding to sucrose solution by extending their proboscis

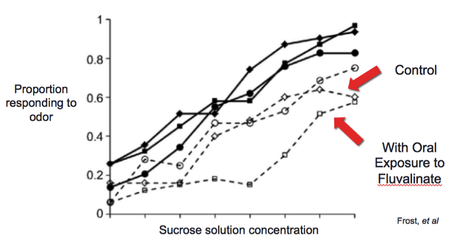

Results from Frost et al., demonstrating oral exposure of fluvalinate causes less bees to respond to PER

Results from Frost et al., demonstrating oral exposure of fluvalinate causes less bees to respond to PER Research using PER shows that sub-lethal doses of several pesticides actually decrease honey bees’ learning ability and memory retention. One of these pesticides is Fluvalinate. Fluvalinate is a varroa treatment that is applied to a colony in the form of strips. This means that it potentially comes into contact with bees of many different ages. While there is already extensive research on Fluvalinate’s effects on PER performance, there is no research on how the age of the bee at the time of exposure impacts the intensity of those effects. That is what I’m trying to tackle in my research project.

Basically, I’m going collect a lot of newly emerged bees and keep them in several small populations (~30 bees), in modified solo cup cages. Different cups will be exposed to Fluvalinate at different ages. Some will be exposed when the bees are 5 days old, some when they are 10 days old, and some when they are 15 days old. These 3 ages roughly represent 3 worker roles in the colony. Five day old bees are pre-nurses, that clean cells and cap brood, 10 day old bees are nurses, that feed larvae, and 15 day old are foragers, than collect pollen and nectar for the colony.

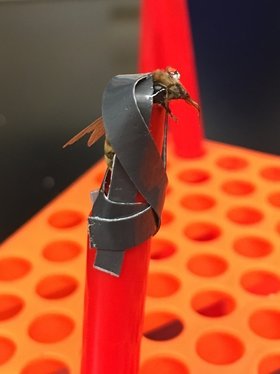

When each group reaches its assigned age of exposure, the cup will be exposed to fluvalinate for only 24 hours, then I will continue to care for and feed them normally (maintaining cage cleanliness, providing sugar solution to eat, etc.) until the cups are 20 days old. I’m planning on using contact exposure to fluvalinate: I’ll be putting a fluvalinate mite treatment strip in each cup, then removing it after the 24 hour exposure period. Once the bees reach 20 days old, the remaining live bees will be individually harnessed (shown below) and conditioned using PER.

Bees harnessed using plastic straw and duct tape

Bees harnessed using plastic straw and duct tape What I’m expecting to see after conditioning is that fewer bees are able to make the correlation between the odor and the sucrose stimulus if they have been exposed to the fluvalinate, regardless of the age when they were exposed. I’m also expecting to see less bees successfully conditioned in the groups that were exposed later in life, as past research indicates that pesticide sensitivity increases with age.

My project is going to take a lot of intricate planning if I’m going to complete it all in the upcoming fall semester (which is my goal). But as complicated as it may be, I can’t wait to get started and learn a lot more about honey bees and the methods with which to study them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed