By Eric Malcolm

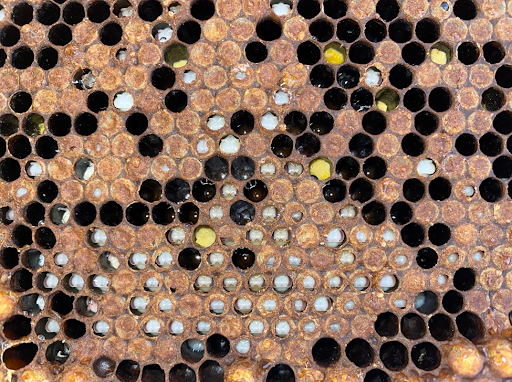

Bald brood is a glaring indicator that something may be amiss in a colony. Many different things can cause bald brood, including infestation with pests like wax moths (as evidenced in the first photo) and small hive beetles.

When wax moth larvae move through the brood comb looking for food, they sometimes move just below brood comb cappings. Worker bees can detect the larval passage and uncap those affected cells, creating a characteristic squiggly line tracing the wax moth's route. While not a cause for alarm, this sign does suggest the colony may be weak. If you see something like this on one of your frames, try gently tapping the frame with your hive tool and see if one of the little buggers pops out!

In the case depicted in the image below, however, the likely culprits are the bees themselves.

When wax moth larvae move through the brood comb looking for food, they sometimes move just below brood comb cappings. Worker bees can detect the larval passage and uncap those affected cells, creating a characteristic squiggly line tracing the wax moth's route. While not a cause for alarm, this sign does suggest the colony may be weak. If you see something like this on one of your frames, try gently tapping the frame with your hive tool and see if one of the little buggers pops out!

In the case depicted in the image below, however, the likely culprits are the bees themselves.

One way bees are able to fend off disease is through hygienic behavior. This involves bees sensing diseased or dead pupa under the cappings, uncapping the suspect cells, and removing the contents. In this picture, you can see many pupal bees exposed where the cappings have been removed. Also visible are several brood areas where both the cappings and the pupa missing, after the pupa have been removed or cannibalized. While various diseases can cause this behavior, in this case, we think it was a result of cold weather (chilled brood). During a cold snap, the population of adult bees in this colony was not large enough to cover all the brood the colony had produced. So, we suspect, after a cold night, the bees clustered but were unable to cover all the brood in the colony to keep them warm. As a result, some died and were removed. However, happily, the next visit showed this colony as healthy and with no signs of bald brood!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed